I’m dusting off the cleats (yes, it’s been a while), as I’ve had a large number of incoming questions regarding what happens to Tesla (TSLA) unsecured debt if or when they file for bankruptcy. This will not be a post about the long list of existential risks facing TSLA at the moment: there will be no commentary about how fundamentally flawed the business is; how they play fast and (very) loose with accounting rules, securities laws and their customers’ lives; how they’ve seen more executive turnover than the first class lounge at London Heathrow; nor how they’ve been running the business on the fumes of fumes for at least the last couple of quarters. For more on any/all of these topics, and a lot more, feel free to mosey on over to Twitter and follow $TSLAQ; or read some excellent blog posts here or here, for example.

Rather, since I consider a TSLA balance sheet restructuring basically a fait accompli at this point, to me the more interesting question than ‘where does the equity go?’ (answer: zero) is what happens to the unsecured creditors. As of the Dec’18 10-K, there was about $5.8bn of unsecured debt with full recourse to the TSLA balance sheet, and today the cheapest of these unsecured bonds trades around 88c on the dollar (the 5.3% ’23 long bond); note also that this category of debt includes the converts trading above par, due to convertible option value even though the strike price is still well out of the money.

I don’t want to spoil the lede, and I should disclose at the outset that I am (significantly) short TSLA stock in various forms (cash equity as well as via put options). But in terms of risk/reward, shorting the bonds may be even more attractive than shorting the common, because – as we shall discuss – I think ultimate TSLA recovery on unsecured debt will be very low (max 33c, likely much lower); you can generally get more leverage on credit shorts than equity shorts (for institutional clients, at least, via CDS); and the payoff on even outright bond shorts is much more asymmetric than shorting the stock (even if TSLA doesn’t file, it is most unlikely TSLA credit improves much in the next 1+ years so the likelihood of a large loss as TSLA credit reprices massively tighter is in my view remote).

Additionally, while not too complicated, TSLA’s cap structure is not exactly clean – so I hope by unpacking it here to demonstrate at least some of the thought process around credit analysis (in particular recovery analysis) and how it can be helpful in guiding not just bond but also equity investment decisions. With that out of the way, let’s dive in…

Step 1) Start with the Balance Sheet

Pretty simple really – any analysis of what creditors (of any stripe) will get depends on what the assets are, right? (Actually its more complicated than this, but let’s work with this standing assumption for now).

As of Dec-18, TSLA’s assets looked like this (the left side), and then on the right, adjusted ONLY for the repaid convert ($920mm that matured Mar-1). We will make other adjustments as we go, but here’s what it looks like for now:

OK, so ~$30bn in gross assets and ~$29bn adjusted for the convert repayment. Sounds like a lot, doesn’t it? Hmm…hold that thought 🙂

2) Isolate assets associated with leases, as well as collateralized against non-recourse loans

Of course, a large portion of TSLA’s assets have been financed by leases – clearly these assets are ‘spoken for’ and unsecured creditors will have no recourse to them (similarly, lessors have no recourse beyond them). At the same time, TSLA has incurred a large amount of so-called ‘non-recourse debt’ (a lot of it related to the SolarCity takeover), which is simply a fancy way of saying certain assets on its consolidated balance sheet have been financed by loans secured against only those assets. Since we want to figure out what’s left for the guys at the bottom of the totem pole, we need to remove all this stuff.

This is where it gets a little tricky. TSLA’s disclosures are not perfect (!) and I have had to make some simplifying assumptions. You can dig through the devilish details in the below table, or you can just rely on the summary of how I have treated most of these obligations:

- short-term and long-term restricted cash are in effect completely consumed by some combination of short-term and long-term build-to-suit (BTS) leases, as well as short-term and long-term residual value guarantees;

- SolarCity related asset-backed securities are collateralized at a 70% average LTV (this is within the range of 65-80% disclosed, occasionally, for some of the transactions, but not all of them);

- The Automotive Asset Backed Notes have only a small amount of overcollateralization (I assume LTV 90%) – this is based on some isolated ABN documentation I have seen suggesting around a 10% O/C cushion.

The below chart summarizes the treatment of all the various leases and non-recourse lending that consumes a good portion of TSLA’s assets, already. Apologies if it’s a little confusing/messy, but the overall takeaway is TSLA has already pledged $5.1bn of consolidated assets against its non-recourse obligations and lease liabilities:

Double-checking this number, page 123 of the 10-K suggests the co has pledged $5.2bn of assets thus far, so I think we are on the right track:

3) Isolate assets associated with secured (recourse) debt

While TSLA has a ton of secured, non-recourse debt, it doesn’t have much secured recourse debt. This makes this part relatively straightforward. There are really only two obligations, one very significant (the Credit Agreement backed by inventories, receivables, and some PP&E, known in the business as an asset-backed loan, or ABL), and one small other obligation.

Again, the precise over-collateralization on the ABL is not public (since the loan docs disclose 85% of ‘eligible’ asset classes ‘less reserves’ is the borrowing base, without making it clear what those reserves are, for example, but given the quality of those underlying assets – inventory, mostly, recovery of which even in clean bankruptcies is still really low, 50% or lower – I think estimating a 70% LTV on the outstanding balance is reasonable if not generous. Hence:

![]()

4) Remove all collateralized assets from existing gross asset side of Balance Sheet

Now we need to put it all together. We simply subtract – from the relevant asset categories, based upon 10-K disclosures as well as reasonable judgement – the collateralized (‘spoken for’) assets, from the gross totals presented in the consolidated accounts. See below for my attempt at this, with some clarifying comments. I have included the original Dec’18 asset side of the balance sheet for ease of comparison. The key number to focus on – at the bottom in yellow – is that post this process of elimination, TSLA’s apparently generous $30bn in gross assets is really only $18bn once existing secured claimants of various types have been removed:

5) Haircutting remaining assets for value in recovery

OK, we are about half way there. Next thing to do is to think through what values the remaining assets may have to creditors. This is the part of the analysis that becomes much more subjective and variable depending on the ultimate form of restructuring (is it a pre-pack filing? Will the business continue as a going concern or not? Will it be liquidated or not? etc). I have personal views as to how this restructuring is likely to play out (to be discussed later), but for the moment I want to emphasize that even if the ultimate form of restructuring is, say, more favorable to TSLA creditors, they will all necessarily apply some conservatism (read: haircuts) to expected asset values in and around any bankruptcy/restructuring process, and by definition unsecured bonds should trade down to/or below (to allow for a risky return to market participants) levels implied by this inherent conservatism. So, the analysis is important and valid, even if by nature imprecise.

That said, you can see below the haircuts I have made to various categories. Some of these haircuts are fairly obvious (intangible assets aren’t worth anything to creditors; recovery rates on inventories and captive non-land PP&E (for example machinery and leasehold improvements would in principle be very low). NOTE ALSO that I have taken a further $1bn out of existing cash – this is NOT because I think the Dec-18 reported cash number is bogus (although I do), but is simply my estimate for the gross cash burn likely to be reported in 1Q (mostly operational, and through restructuring cost, not W/C build), so I think this is a defensible adjustment and may end up being conservative.

As you can see, even the $18bn gross available to unsecured creditors could end up being more like $9.5bn, or less, post recovery impairments to stated asset values on the last balance sheet:

6) Estimating unsecured claims…

OK so we’ve figured out the asset side (‘assets available to unsecured creditors’), but what about the creditor claims themselves?

Again, this is an area where the form of the restructuring could have large implications for ultimate recovery. For example, in any kind of ongoing-business situation, trade claimants (accounts payable, accrued expenses, a few others) would effectively be treated senior to all other claimants simply by the fact that unless they get paid the company will go into liquidation. In the below I do NOT assume that is the case – in other words my base case assumption is all unsecured claimants get treated equally, after administrative claims, as would be the case in a liquidation. As we shall see, this is likely an assumption that FAVORS non-trade unsecured creditors in this case (ie, bondholders), but in any case I will expand on my reasoning for this in a little more length in a moment.

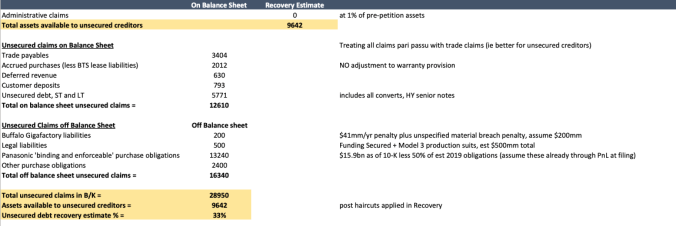

For now, we simply need to tot up all the remaining balance sheet liabilities that are neither leases, nor non-recourse debt, nor secured recourse debt. Then – and this is very important – we need to estimate the off balance sheet liabilities that become unsecured claimants post filing. Again, another area of huge judgement required (estimating the liability related to all the shareholder lawsuits re ‘Funding Secured’, for example), but once again, I have tried to be as ‘pro-creditor’ as possible in my approach. Even so, the following large items make it onto the unsecured claimants list:

- trade claims (about $6bn);

- customer deposits ($0.8bn) – yes this is simply an unsecured claim (gulp);

- unsecured debt ($5.8bn left post recent convert repayment);

- Panasonic purchase obligations ($13.2bn under ‘binding and enforceable contracts’, clearly the massive elephant in the room);

- Other purchase obligations ($2.4bn);

- My estimates for the NPV of the Buffalo Gigafactory breakage cost ($200mm) and legal liabilities ($500mm) – both of these numbers probably end up higher.

NOTE I have not attempted to ‘true up’ the warranty provision or make any other grand assumptions re the state of the numbers, today; rather I am simply trying to assess where the numbers naturally fall as they currently stand, and see what that says about recovery value before anything (else) goes wrong.

As a result, we get something like this:

Hence, my conclusion that unsecured recovery tops out at 33c and in reality is likely to be much, much lower. Perhaps it’s worth expanding on why that may be the case.

If you’ve been following closely thus far, you can see that the residual assets available to the unsecured class are essentially cash, then SolarCity assets and then PP&E. First, the easy part: even if we thought the $3.7bn cash balance (pre convert repayment) was ever real, the chances of that being there when or if they file (given how Musk is barrelling the company right over the cliff) is, let’s say, quite low. And as for the fixed assets – as a general rule, recovery values on fixed plant tend to undershoot on the downside. Simply put, hard assets like buildings and special purpose machines are not worth anywhere near as much to a new buyer as they are to an ongoing business. Finally, when it comes to the SolarCity assets, since SC was such a liberal user of asset backed financing when it was a going concern, I find it hard to believe there is much ‘real’ (read – to a third party) asset value in the un-collateralized assets today. If there were, I believe they would have already been siphoned off for additional liquidity by now…

Liquidation or DIP+Restructuring?

…Which leads us to a further point about why, to my mind, this is more likely to be a liquidation scenario than a going-concern restructuring. In order to restructure and keep the business is operation, TSLA, once it files, will need a MASSIVE debtor-in-possession (DIP) financing – maybe $3-5bn, by my estimate, simply to fund ongoing operations. This may not be impossible to conceive, but consider the following:

- TSLA runs massively negative working capital ($1.5bn or so currently by my estimate) and has $6bn of trade claimants, today. Also, many of those creditors have given back large rebates to TSLA simply to allow them to survive until now; many of them have not been paid on time, ever. How much of that DIP goes straight out the door to keep the lights on – $2bn? $3bn? Why wouldn’t cash on delivery conditions exist for any go-forward business post-restructuring without a massive decrease in credit extended by suppliers?

- DIPs are generally only provided when management remains in charge. I find it hard to believe Musk & co will be entrusted to run the company if/when it files (especially if there are fraud implications, which also seem highly likely). That necessarily makes it harder to get a DIP;

- Keep in mind that Musk and co still run the company today and by the time it actually files, even if this is just in a couple of quarters, the liquidity/asset quality/brand quality of whatever is left is, judging by current events, likely to be exponentially worse and thus less salvageable (from the perspective of any potential new credit provider);

- While not impossible it is generally harder to get a DIP in cases where there may have been malfeasance/fraud (in TSLA’s case, this could crop up in a multitude of different ways);

- A DIP would have to prime the other secured lenders (currently the banks backing the ABL). While if these same lenders provided the DIP (as often happens) this may be doable, consider that – as we have discussed at length – there aren’t really many other assets left to the estate worth collateralizing that gives the ABL lenders reasonable security that their position is not being made worse than a liquidation (where they would most certainly be made whole);

- A large DIP probably only accompanies a search for a buyer of part/all of TSLA. That means financing is contingent upon a third-party being willing to underwrite, say, the value of TSLA’s brand – such as it is post the price cut abomination that Musk unfurled last week – but at the same time likely means an end to the Model 3 (which essentially is what killed the company). However to my mind there are very few ways to keep the company going and viable as a brand, without continuing to service/repair/warranty the 250k+ Model 3 lemons on the road (imagine the brand damage of that approach…). But what third-party buyer is going to be willing to underwrite that open-ended, multi-year expense?

None of this is to say a DIP, and a sale or recapitalization as a going concern is impossible (hell, Enron and Worldcom both got DIPs) – just that in this particular case I think it is clearly not the base case outcome.

But the overriding takeaway is simply this: even if you think it DOES remain an operating concern and they DO get DIP financing then the unsecured recovery will most certainly be a lot lower – since something like $3-5bn of super-senior secured financing will come in ahead of the unsecureds; and that new cash likely makes its way, mostly straight out the door to other unsecured creditors (trade claims) before the bondholders (and maybe Panasonic, for that matter – yet another reason why the DIP solution may not be forthcoming). Meaning, of course, if somehow a DIP does get done, unsecured recovery will be much, much lower than the 33c best case this exercise has suggested.

Disclosure: short TSLA everything (stock, straight bonds, converts, the lot).

I have one question. Where did you get the “$13.2bn under ‘binding and enforceable contracts’”?

I’ve been looking for the same number in their latest 10K but was unable to find the same number.

Btw, this is what I found in the latest 10K

> (ii) $15.69 billion in other estimable purchase obligations pursuant to such agreements, primarily relating to the purchase of lithium-ion cells produced by Panasonic at Gigafactory

Just wanted to know for my educational purpose.

Pingback: Taking stock of 2019: idea performance and thesis updates | Raper Capital

Pingback: Tesla Unsecured Debt 30 Cents On The Dollar If You Are Lucky - ValueWalk